By Moloy S Baruah, M. Mokidul Islama & Meghna Sarma

Lumpy Skin Disease (LSD) is emerging as one of the most significant threats to cattle health and rural livelihoods across India, including the northeastern state of Meghalaya. With its rapid spread, especially during the monsoon season, and its impact on milk production, animal welfare, and rural income, farmers must be fully informed and prepared to tackle this growing challenge. The disease, though not new globally, is relatively recent in India and poses serious concerns for livestock-reliant communities in the hill regions of the Northeast. Lumpy Skin Disease is a viral disease that affects cattle and, in some cases, buffaloes. It is caused by the Capripoxvirus, which belongs to the same family as the sheep pox and goat pox viruses. The disease is characterized by large, firm nodules on the skin, high fever, swollen lymph nodes, nasal discharge, eye infections, and in many cases, reduced appetite and significant loss in milk production. Some infected animals may also suffer from difficulty in movement due to swelling in the limbs and joints. In severe cases, secondary infections can occur, and if not treated early, the disease can lead to permanent damage to the animal’s health, infertility, or even death.

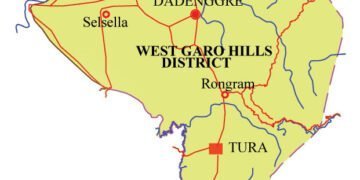

Though LSD does not spread to humans, it poses a major threat to the livestock economy and to families whose livelihoods depend on dairy farming and cattle rearing. LSD is spread primarily through biting insects such as mosquitoes, ticks, stable flies, and other blood-sucking insects that thrive during the monsoon and post-monsoon periods. The virus can also spread through direct contact with infected animals, and indirectly through contaminated feed, water, equipment, clothing, or animal handlers. Once one animal in a herd is infected, there is a high risk of the disease spreading quickly unless proper precautions are taken. The incubation period for LSD is around 4 to 14 days, and infected animals must be isolated immediately to prevent further spread. The disease was first reported in India in 2019, and in just a few years, it has spread rapidly across the country. The 2022 outbreak was the worst in recent history, affecting more than 2.5 million cattle across 15 states, including Rajasthan, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Punjab, and Uttar Pradesh. Thousands of animals died, and milk production dropped significantly in some regions. The government and veterinary authorities responded with emergency measures, including vaccinations, isolation zones, and awareness drives. Since then, India has ramped up its efforts to monitor and control LSD outbreaks through state veterinary departments and central agencies. In 2025, fresh outbreaks have again been reported in several states, and cases are now being confirmed in parts of Meghalaya, especially in West Garo Hills, West Khasi Hills, Ri-Bhoi, and bordering districts. Due to the region’s warm, wet climate and high vector population, the risk of the disease spreading quickly is high. Many cattle owners in Meghalaya have limited access to veterinary services, and the movement of livestock between villages and weekly markets further increases the possibility of transmission. Unvaccinated animals are especially at risk, and once the disease enters a herd, the financial losses can be devastating for small-scale farmers. To respond to the situation, the Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Department of Meghalaya has initiated active surveillance and is organizing vaccination drives using the Goat Pox vaccine, which, though originally developed for goat pox, has shown good effectiveness against LSD. Farmers are being urged to get their animals vaccinated as a preventive measure, even if there are no cases in their immediate area. Vaccination, however, is not enough on its own – other essential steps include:

- Immediate isolation of sick animals from the herd.

- Regular cleaning and disinfection of cattle sheds, feeding equipment, and water containers.

- Control of insect populations using smoke, neem-based repellents, mosquito nets, and fly traps.

- Avoiding the movement or trade of animals from infected areas to healthy zones.

- Prompt reporting of suspected cases to the nearest veterinary officer or livestock assistant.

Farmers should also be trained to recognize the early symptoms of LSD and encouraged to act swiftly rather than waiting for the condition to worsen. In most cases, early veterinary treatment, supportive care (fluids, anti-inflammatory drugs, wound care), and good hygiene practices can help animals recover fully. Dead animals must be buried properly and not left in the open, as carcasses can attract more vectors and spread the disease further.

The government is also working on the development and rollout of Lumpi-ProVacInd, India’s first indigenous vaccine specifically targeting LSD, developed by the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) in collaboration with Indian Immunologicals Limited. This vaccine is expected to be introduced across high-risk areas in the coming months, further strengthening the country’s fight against LSD.

In conclusion, Lumpy Skin Disease is not just a veterinary issue – it is an agricultural emergency, particularly for regions like Meghalaya where livestock forms the backbone of rural life. Protecting our cattle means protecting food security, income, and the traditional way of life for thousands of families. With increased awareness, vaccination, timely reporting, and support from government and community networks, LSD can be controlled. Farmers are urged to stay alert, spread the word in their villages, and act quickly at the first sign of infection. Early action today will ensure healthy herds and secure livelihoods tomorrow.

(The writers represent the Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Ri-Bhoi, Indian Council of Agricultural Research Complex for North Eastern Hill Region, Umiam, Meghalaya)