By Dipak Kurmi

India enters 2026 confronting a neighbourhood marked by turbulence, fragility, and unresolved conflict, a reality that has steadily reshaped its strategic environment since independence. Surrounded by states facing internal instability or governed by unelected and contested regimes, India’s external periphery remains one of the most complex in the world. Persistent cross-border terrorism emanating from Pakistan, the systematic marginalisation of minorities, particularly Hindus, in Pakistan and Bangladesh, and renewed unrest along the Indo-Myanmar frontier together underscore a hard truth: India’s security challenges are deeply embedded in the political and social dynamics of its neighbourhood. These pressures are not episodic disruptions but enduring features of a volatile regional landscape that demands constant vigilance, adaptive strategy, and institutional resilience.

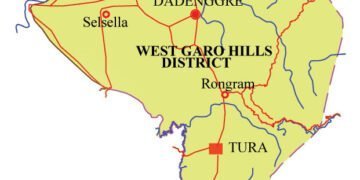

Along the Line of Control, the rhythms of daily life have once again adjusted to uncertainty. Villages near the frontier have learned to live with heightened alertness, where evening movements are cautious, unfamiliar sounds invite suspicion, and drone sightings are discussed with weary familiarity. These are not abstract security concerns but lived realities that shape social behaviour and economic activity. On India’s eastern flank, exporters in West Bengal describe growing unpredictability in cross-border trade with Bangladesh, as political unrest and administrative disruptions across the border quickly translate into delayed shipments and cancelled orders. In the Northeast, districts bordering Myanmar remain tense, with instability spilling over from that country’s internal conflict and complicating security management. These local experiences reflect a wider regional pattern in which political instability, economic stress, and armed conflict are intensifying simultaneously across South Asia and India’s eastern periphery.

Pakistan’s internal trajectory remains a central concern for India’s security calculus. The country has witnessed a sharp deterioration in internal security, with militant attacks rising and extremist violence resurging, particularly from western regions. Groups linked to the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan and transnational extremist networks have intensified operations, while Balochistan continues to simmer with separatist violence. Attacks on security forces and infrastructure projects, including those associated with the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, highlight the depth of internal fragmentation. For New Delhi, these developments reinforce long-standing concerns that Pakistan’s domestic instability does not remain contained within its borders but generates indirect pressure along India’s western frontier through proxy threats and cross-border militancy.

Bangladesh, long viewed as one of India’s more stable neighbours, is undergoing a period of political flux following leadership changes and sustained public mobilisation. While state institutions continue to function, the transition has been accompanied by episodes of unrest and a more visible role for Islamist political actors. These developments carry tangible implications for India, particularly given the depth of economic interdependence between the two countries. Bangladesh is India’s largest trading partner in South Asia, with annual trade exceeding eleven billion dollars and land routes playing a critical role. Disruptions at land ports, transport corridors, or administrative systems have immediate consequences for exporters and logistics networks in West Bengal and the Northeast, underscoring how political uncertainty across the border can rapidly translate into economic stress within India.

To the east, Myanmar remains locked in a protracted civil war that shows little sign of resolution. The military junta continues to face resistance from multiple armed groups, leaving large areas of the country contested and governance fragmented. For India, the implications are direct and persistent. Cross-border security challenges along the northeastern frontier have intensified, raising concerns over arms trafficking, organised crime, and the movement of insurgent elements through poorly governed spaces. The conflict has also complicated humanitarian considerations, as displacement and instability affect border communities on both sides. Unlike short-lived crises, Myanmar’s civil war represents a structural security challenge that demands sustained attention rather than episodic responses.

Sri Lanka presents a different but equally instructive case of neighbourhood fragility. Although the country has stabilised from the depths of its 2022 economic crisis, vulnerabilities remain pronounced. Debt restructuring agreements and multilateral support have improved liquidity conditions, yet economic growth remains modest and public finances constrained. Climate-related shocks, including cyclones and flooding, continue to impose repeated fiscal and infrastructure costs, testing the resilience of an already strained economy. Sri Lanka’s dependence on external assistance has sharpened strategic competition among its partners, as economic vulnerability increasingly translates into diplomatic leverage. For India, this underscores how economic distress in neighbouring states can quickly assume strategic significance.

The risks emanating from India’s neighbourhood are cumulative rather than compartmentalised, converging across security, economic, and strategic domains. On the western front, Pakistan’s internal turmoil has coincided with increased militant activity, reinforcing the persistence of proxy threats despite periodic ceasefire arrangements. In the east, Myanmar’s conflict complicates border control and internal security in sensitive northeastern states. The strategic importance of the Siliguri Corridor, India’s narrow land link to the Northeast, has grown as instability simultaneously affects both Bangladesh and Myanmar. This convergence reduces India’s ability to sequence challenges or focus on a single front, instead demanding a multidirectional security posture.

Economic exposure has emerged as a frontline concern alongside traditional security risks. India’s trade with Bangladesh, heavily dependent on land routes, illustrates how political unrest or administrative disruption across borders can have immediate and disproportionate effects on regional supply chains. Sectors such as textiles, agriculture, and small-scale manufacturing, often dominated by smaller firms, are particularly vulnerable to land-border interruptions. Unlike maritime disruptions, which can sometimes be rerouted or absorbed, land-border volatility directly affects livelihoods and regional economies, linking neighbourhood stability to domestic economic resilience.

Overlaying these challenges is an intensifying layer of strategic competition. Economic stress in neighbouring states often increases reliance on external financing, infrastructure development, and emergency assistance, drawing in global and regional powers with competing interests. In the Indian Ocean and the Bay of Bengal, ports, logistics hubs, and connectivity projects now carry strategic weight alongside their commercial value. As a result, neighbourhood instability rarely remains a purely local issue, instead intersecting with broader geopolitical rivalries that shape India’s strategic environment whether New Delhi actively intervenes or not.

India’s response to this complex landscape has been shaped by differentiation rather than uniformity, reflecting the varied conditions across its neighbourhood. In Sri Lanka, India has played a visible role in crisis response and recovery, extending emergency assistance after climate disasters and participating in stabilisation efforts during the debt crisis. These measures have not only supported economic recovery but also reinforced India’s position as a reliable regional partner during periods of acute vulnerability. With Bangladesh, India has maintained diplomatic engagement and trade continuity despite political uncertainty, sustaining security cooperation and institutional dialogue even as businesses report heightened volatility linked to domestic developments across the border.

Along the Myanmar frontier, India has prioritised border security coordination and humanitarian support in cooperation with state governments. These efforts address immediate pressures but are constrained by the protracted nature of the conflict, which ensures that security challenges remain persistent rather than episodic. In the case of Pakistan, India has sustained a posture of deterrence and preparedness, investing in infrastructure upgrades, surveillance enhancements, and intelligence coordination along sensitive sectors. This approach reflects assessments that instability within Pakistan continues to pose indirect risks regardless of formal diplomatic engagement.

At the regional level, platforms such as BIMSTEC and Indian Ocean cooperation mechanisms offer frameworks for dialogue and coordination, though their capacity to respond swiftly to overlapping crises remains uneven. What emerges from developments across India’s neighbourhood is a set of clear patterns. Instability is increasingly multidirectional, arising simultaneously from the west and the east. Economic and security dynamics are tightly intertwined, with trade disruption and internal unrest often stemming from the same underlying political and economic shocks. Crucially, state capacity in neighbouring countries matters as much as intent, as weak institutions and domestic volatility generate spillover effects that India must manage irrespective of diplomatic goodwill.

The past year underscores that India’s neighbourhood challenge is less about isolated crises and more about structural instability across adjoining states. Pakistan’s internal security trajectory, Bangladesh’s political flux, Sri Lanka’s fragile recovery, and Myanmar’s unresolved conflict are driven primarily by domestic factors beyond India’s direct control. Yet their interaction with India’s geography, trade routes, and security imperatives ensures that these stresses are felt in New Delhi regardless of policy choices. The neighbourhood, once seen primarily as a zone of influence, has increasingly become a zone of exposure.

As India navigates this environment, its strategic posture in 2026 is shaped not by the ability to resolve neighbours’ internal problems, but by how effectively it absorbs and buffers their spillover effects. Security preparedness, economic resilience, and diplomatic bandwidth have become defining features of India’s external engagement. History reminds us that national security extends beyond borders and military assets to include collective resolve and the courage to act in defence of national interests. In this context, Tipu Sultan’s words, that it is better to live one day as a lion than a hundred years as a jackal, resonate not as a call for recklessness, but as an enduring reminder of firmness, unity, and the unwavering commitment required to safeguard India’s sovereignty in an increasingly uncertain neighbourhood.

(The writer can be reached at dipakkurmiglpltd@gmail.com)