The year 2022 has been a year of records for rainfall in the State. On the 17th of June 2022, Mawsynram recorded 1003.6 mm of rainfall in a single day breaking the record it had previously held since 1940. On the same day, Sohra, its eternal rival, also recorded the maximum daily rainfall of 972 mm which was the highest for the last 27 years. For the rainfall enthusiast this is very exciting news. This includes those who want to promote tourism in the State. Such a unique phenomenon enhances the reputation of the region as being one of the top ecotourism destinations not just in India but throughout the world.

But not everyone is thrilled with the records being broken. For many, the heavy rainfall in the State was a curse rather than a blessing. Roads were washed away and landslides were a common occurrence in many parts of the State. Precious lives were also lost in some of them. The inclement weather further exposed the many cracks in the State’s infrastructure which already was apparent in the collapsed dome incident among others. One sector where the impact of rainfall has been severe but which failed to get much mention is the agricultural sector.

It was during that the same time, the author was traveling to Nongtraw, Dewlieh, Ladmawphlang, Umsawwar and Nongwah, all located in East Khasi Hills for ‘Participatory Needs Assessment Workshops’ facilitated by NESFAS (North East Slow Food and Agrobiodiversity Society) Research and Knowledge Management team. In fact, on 17th June 2022 when Sohra broke the rainfall record, the author was in one of villages in the area. Ferocious downpour and strong howling winds greeted him and his team as they climbed down the 3000+ steps to arrive at the village. It was an exhilarating, but also at the same time, a very frightening experience.

Coming back to the workshop, among the many themes that were discussed with the local community using the VIPP (Visualisation in Participatory Programmes) toolkit, the changes in weather conditions and variations in agricultural yield over the last few decades were very prominent topics of discussion. The common consensus which emerged from these discussions was the realisation of growing uncertainty of weather patterns and a general decline in yield of different crops. This is particularly so in the case of potato which production was reported to have suffered greatly because of the incessant rainfall. Household food security is going to be adversely affected by this in two ways. Farmers grow the crop for self-consumption as well as for selling it in the market.

Firstly, the decline in own production is going to reduce the amount that can be consumed at home. Secondly, since there will be loss of income from the sales that did not happen, it will reduce the cash that would have been available to buy substitute foods from the market. In both the scenarios, household food security will be greatly impacted. In Umsawwar (a village in Mawkynrew Block) when the NESFAS team and those present from the community in the workshop were exploring potential solutions to tackle the problem, one of the community members Kong Anjela Nongrum stood up and explained to the NESFAS team the history of potato cultivation in the village.

An upcoming book ‘Iron Industry and Limestone Trade of the Khasi-Jaintia Hills of Meghalaya’ by Bobby Wycliff Wahlang, Assistant Professor in Ri-Bhoi College has given a detailed description of how potato was introduced in Meghalaya. The crop was brought by David Scott who, as an Agent to the Governor-General in Council at Calcutta, arrived in the hills in 1823. This was done as part of his mission to expand British policy of commercialisation of agriculture by introducing new crops. By the 1940s large quantities of potato were exported to markets as distant as Calcutta. Although initially an exotic crop, numerous landraces were subsequently developed by the local indigenous farmers improving the adaptability of the crop to the region.

In East Khasi Hills, the ‘Participatory Agrobiodiversity Mapping Exercise’ undertaken by NESFAS which included the villages of Umsawwar and Nongwah documented an average of six potato varieties with the maximum of 15 varieties recorded from the village of Khapmaw in Mawkynrew block. Jhum or shifting cultivation is the main farming system practiced in this village. The diversity is therefore not surprising. In fact, out of the 15 varieties, 12 are growing in shifting cultivation plots again highlighting the immense diversity that the system harbours. This does not include the varieties that farmers had developed but have been lost over time as other varieties replaced them. In Umsawwar, the loss of one particular potato variety is proving to be very crucial in terms of long term sustainability of the crop in the village in light of changing weather conditions.

Previously the village used to grow a local variety known as Sohlah Ltot. However as the farmers chased the market and adopted new varieties bought from outside, the local variety was lost. An important feature of this erstwhile variety was its resistance to heavy rainfall which even in normal years is quite heavy in the area. Though the yield is higher, the new varieties are not very resilient to stress in climatic conditions. This was also the finding from the ‘Participatory Agrobiodiversity Mapping Exercise’ in which the community had reported that the varieties grown in the village are not highly resilient to extreme weather conditions. The heavy rainfall this time around has brought that out very starkly.

Having realised from the discussion how important quality seeds, especially those that are resilient to extreme weather conditions, are for adaptation to climate change, Kong Anjela Nongrum assured that she is going to replant the old variety. No one in the village, however, has the seeds. Fortunately (L) Kong Niañ Nongbri’s family in the neighbouring village of Ksanrngi is still growing the said variety. Kong Anjela Nongrum is now going to approach the family to either buy or exchange the particular seed so that she can plant them in the fields. NESFAS is going to facilitate the process. It is hoped that the reintroduction of the ‘Sohlah Ltot’ will bring about stability in production and improve the resilience of the local food system to climate change.

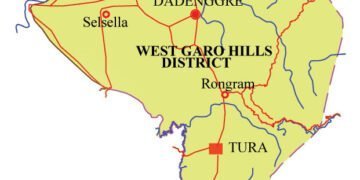

A few days ago, the author was in discussion with the General Secretary of the Hill Farmers’ Union where seed was an important point of discussion. According to the General Secretary, while the Government of Meghalaya has banned the use of chemical fertilisers, it has not restricted the use of hybrid seeds. Since such seeds are dependent on external inputs it has created difficulties for the farmers. Promotion of local seed varieties therefore could be a potential solution. An example of this is the launching of the Rice-Centric Community Seed Bank in Sadolpara, West Garo Hills by James Sangma, Forest and Environment Minister of the Government of Meghalaya facilitated by the NESFAS in association with ELP Foundation.

This seed bank will focus on preserving and propagating the local rice varieties, which in the words of the Minister having survived for such a long time must have high resilience to climate change. The research done by NESFAS and feedback received on the ground confirms this to be so in the case of potatoes. It certainly will be so for rice as well. Hopefully this is a prelude to more such initiatives for conserving and strengthening the traditional seeds developed by the indigenous communities of Meghalaya. This can be a gift not just to the farmers of Meghalaya but to the whole world in its effort to strengthen the resilience of the food system to climate change.

The writer is a Senior Associate, Research and Knowledge Management at NESFAS and can be reached at bhogtoram.nesfas@gmail.com